Anatevka, Jason Gwasdoff, and Jimi Hendrix

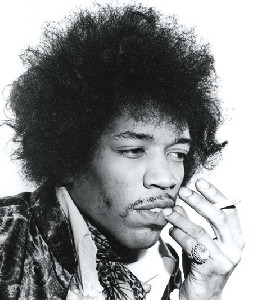

Last night I had the strangest dream: I was a teacher for undergraduates at a university, in which the classroom was long and narrow, almost like a church. I was a guitar instructor on the first day of school. It wasn't clear whether I was instructing students in playing guitar or whether it was about its history initially, but before long, it turned to the spirituality of guitar. One student brought a guitar with alternate tuning which I had to commandeer and restring. Another talked about how they thought the greatest guitarist of all time was Jimi Hendrix (perhaps this entered my dreams because of something I saw recently, which fantasized how incredible a heavenly band would be by combining Jimi, Keith Moon of the WHO, and all the other greatest rock n' roll musicians). Finally, Melissa Morton, one of my actual students, was present. She is, indeed, a guitar student at USC.

I could feel from this experience that as a rabbi, all the students there thought I was totally out of context teaching guitar. However, in my dream, it was obvious to me that it made perfect sense. In fact, I woke up with resentment that I had to explain the linkage between music and being a Jew.

My first exposure to guitar came in a Jewish context. First Rabbi Jason Gwasdoff when I was in Kindergarten at Temple Ahavat Shalom, and then later at Camp Swig under the gaze of the talented Joel Siegel, I was mesmerized by the auditory and spiritual experience of songleaders teaching me music. Jason would hop from classroom to classroom spreading his wares, and I distinctly remember the throwaway riff he used for "Bim Bam," which I use to this very day ("cheery-beery-beery"). Joel Siegel, meanwhile, was the coolest guy I had ever met, with his twelve-string (Fender? Or was it a Martin?) guitar and kick-ass erudition on the axe. "Shomrim's looking out for you," to the melody of "Queen of Hearts" by Juice Newton. Swig continued to knock me over with such luminaries as Gordon Lustig and Jonathan Kraus, who took personal interest in me when we went shopping for cd's in Westwood years later, and the now-anonymous songleader named "Debbie" or "Debby," who owned what soon became my model of guitar, a Takamine 360-s. I wanted to be her, or at least have my guitar sound like hers. My awe of the songleaders was so immense that I never thought I could measure up and thus never tried out as a songleader at camp. Years later, I realized that either songleading has declined or I was delusional regarding both the technical skill and sense of spiritual connectedness that my songleaders at camp had. I could have easily been as great as these songleaders. As my father-in-law once said, wouldn't it be great to have a gospel choir urging you on every time you tried something? That's called "camp."

My Jewishness was born less out of lox and more through our rich musical tradition. Perhaps this is why I chose the rabbinate? The culture was never kitch, it was never mockable for me; it was always about meaning, intellect, exploration of the possibilities for the world, hope. Guitar took me out of my childhood isolation and loneliness and gave me a tool to connect with others and with my (other) lifelong partner, Judaism.

Would I have become a Rabbi had I not learned, through music, what "Rabbi Yehuda" (sic.) taught, long ago? Al Tistakeil b'kankan, elah b'masheyesh bo: Don't look at the bottle, but rather what is within it? Or Kum Bachur Atzeil v'tze l'avodah: Get up you lazy kid and get to work? Or the other scores of so-called lyrics which reflect our people's collective wisdom and wit? At camp, amid the redwood grove, Holocaust Memorial, and the migdal-mayim up the hill, with its hippie-painted sides portrayed on the cover of "Tov Lanu Lashir," the first Camp Swig album produced before I had a Swig-consciousness, I fell in love with Judaism. There was one day back in 1985 or so, where during free time, I walked all over camp, looking for total isolation with my guitar and songbook, hoping to offer, b'kol ram, the cool mix of Debbie Friedman's "Dodi Tzach" and "Kumi Lach," which Wally Briskin or someone else taught me went so well together. I must have come across to passersby as a complete freak, strolling about with my Takamine with a glow on my face, oblivious of time.

Recently, a coworker reacquainted me with the soundtrack of "Fiddler on the Roof," the great fifties musical which sounds even better today than it did in my childish ears years before:

If I were rich, I'd have the time that I lack

To sit in the synagogue and pray.

And maybe have a seat by the Eastern wall.

And I'd discuss the holy books with the learned men,

several hours every day.

That would be the sweetest thing of all.

How extraordinary our culture is! The sweetest thing of all, Zero Mostel notes, is learning! Yes, previous lyrics talk of creating stairwells going up and down "just for show" and lots of farm animals, but to end its way with the idea that in our texts is the answer to life's meaning is both delightfully refreshing for the poor among us and a testament to the old Yiddish axiom (proffered by HUC's Leonard Kravitz on mulitiple occasions): The Oilem es a goilem, The world is an illusion.

I couldn't listen to the song, "tradition," without immediately becoming farklempt. I am not sure why: Is it the sense of reciting m'chayeh meitim for hearing a musical acquaintance long out of mind? Is it a recapturing of my childhood, when I would sit in the living room amid record covers reading/listening to the albums on a very cheap yet sacred musical altar known as our record player (Gosh, I miss that old stereo cabinet, destroyed in my family's November 1995 fire)? Is it a sense that they don't make music like they used to? Or is it the lyrical message, that tradition is a great thing, even if we don't know where it originates? I'm sure it is a combination of many factors, but integrated in all of this farklemptkeit, if that's a word, is a sense of pain that Judaism has been my greatest source of inspiration and I can't seem to convince enough people that it is more than just an external idea, a lame opiate for the masses meant to dull our senses; rather, without it I would not be alive. Without it, the world would have long ago imploded.

I couldn't listen to the song, "tradition," without immediately becoming farklempt. I am not sure why: Is it the sense of reciting m'chayeh meitim for hearing a musical acquaintance long out of mind? Is it a recapturing of my childhood, when I would sit in the living room amid record covers reading/listening to the albums on a very cheap yet sacred musical altar known as our record player (Gosh, I miss that old stereo cabinet, destroyed in my family's November 1995 fire)? Is it a sense that they don't make music like they used to? Or is it the lyrical message, that tradition is a great thing, even if we don't know where it originates? I'm sure it is a combination of many factors, but integrated in all of this farklemptkeit, if that's a word, is a sense of pain that Judaism has been my greatest source of inspiration and I can't seem to convince enough people that it is more than just an external idea, a lame opiate for the masses meant to dull our senses; rather, without it I would not be alive. Without it, the world would have long ago imploded. How to convey to students why Judaism matters? More personally, how do I link my knowledge of Jewish music to the Jewish fates of my students? I think this is one of the great questions that I need answered.

May God bless Jason Gwasdoff, Phil Nadel, David Meyers, Jonathan Kraus (especially!), Joel Siegel, Debbie, Esther and Harvey Saritsky (who gave me my first guitar), my parents (who beared the awful playing initially), Gordon Lustig, Peter/Paul/Mary (in that order), Debbie Friedman, Danny Friedlander and Jeff Klepper, and the long, long list of inspirations who taught me that music was the secret to gnosis, d'veikut, "a politics of meaning."

May the Lord protect and defend you.

May the Lord preserve you from pain.

Favor them, Oh Lord, with happiness and peace.

Oh, hear our Sabbath prayer. Amen.